Learn about Mechanical Engineer Training

Outline:

– Foundations: math, physics, design principles

– Hands-on labs: materials, manufacturing, prototyping

– Digital fluency: CAD, simulation, data

– Industry exposure: internships, co-ops, capstones

– Professional growth and conclusion: ethics, licenses, lifelong learning

The Academic Core: Turning Fundamentals into Engineering Judgment

Mechanical engineer training begins with a disciplined study of fundamentals that convert curiosity into reliable judgment. A typical degree path is built on mathematics (calculus, differential equations, statistics), physics (mechanics, electricity and magnetism), and core engineering sciences (statics, dynamics, thermodynamics, fluid mechanics, materials science, and control systems). These subjects are not disconnected islands; they form a network of concepts that let you move from a word problem to a defensible design decision. For example, a pump selection task draws on fluid mechanics for head loss estimates, thermodynamics for efficiency considerations, and statistics to size for variability in demand. Programs often require roughly four years of study, general education plus engineering credits, and a progression from theory to increasingly open-ended design courses. The aim is not to memorize equations, but to develop a way of thinking: express a problem, simplify responsibly, model it, compute, test the sensitivity of assumptions, and communicate a rationale.

The most effective curricula also cultivate engineering judgment by sequencing learning in layered loops. Early labs demonstrate fundamental properties—stress-strain curves, heat transfer coefficients, Bernoulli’s principle—while later projects integrate them into design choices that trade cost, performance, reliability, and sustainability. Students learn that “correct” is not a single number; it is a well-defended range justified by data and constraints. Two students might size different heat exchangers and still both succeed if their assumptions, safety margins, and manufacturability considerations are transparent and consistent with a client’s priorities. This nuance is essential: it mirrors real practice, where uncertainty is managed rather than wished away.

What distinguishes a robust academic foundation? Consider these building blocks embedded in many respected programs:

– A scaffolded math-physics core aligned with concurrent engineering courses to reinforce learning.

– Gateway labs that convert theory into measured behavior and introduce uncertainty analysis.

– A mid-program design studio that forces choices under constraints rather than ideal conditions.

– Exposure to ethics and standards, teaching responsibility for public safety and the environment.

– Communication training through reports, memos, and presentations aimed at non-specialists.

Together, these elements cultivate the mindset needed to assess risks, justify trade-offs, and carry a design from blank page to production drawing.

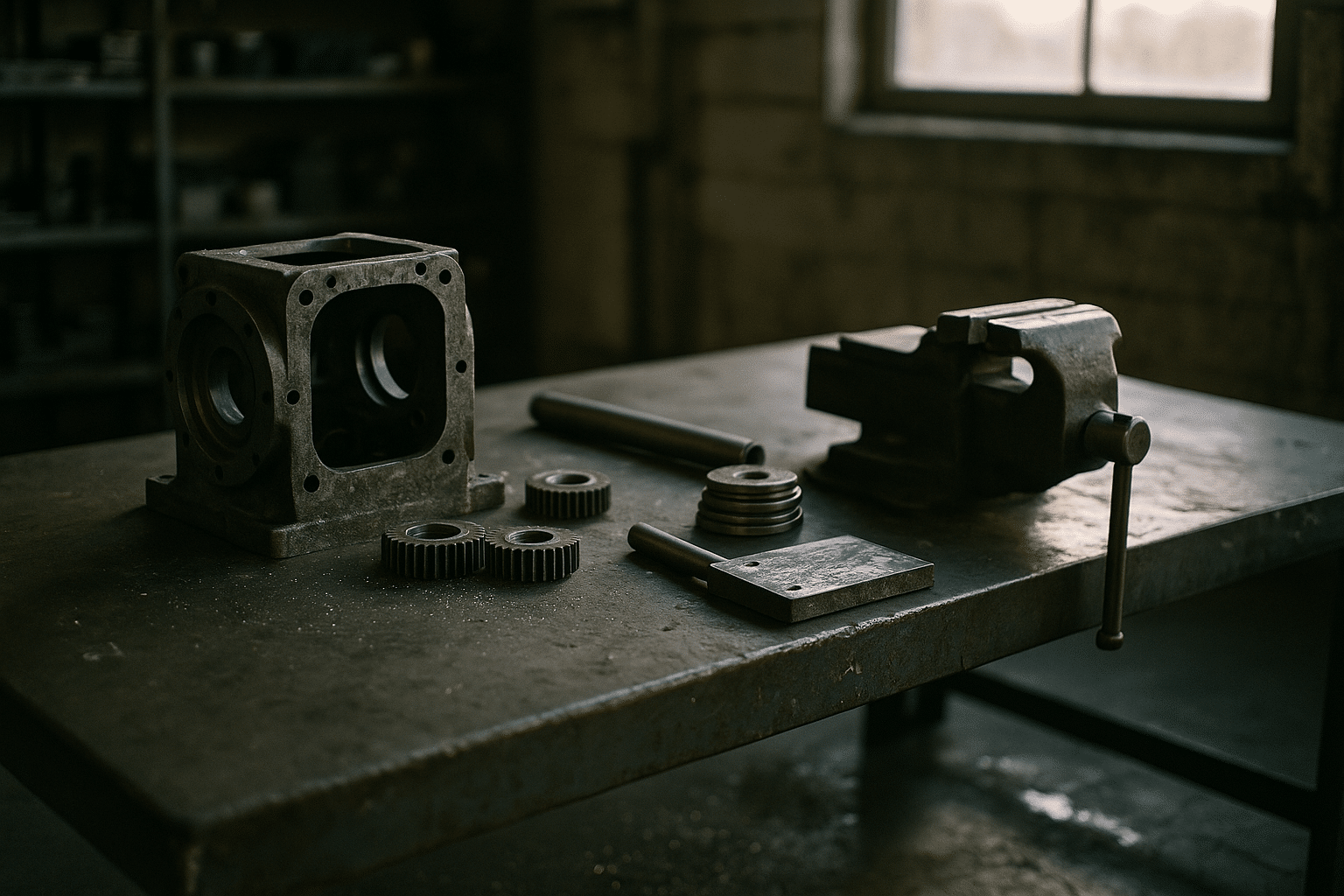

Workshops and Labs: From Tools to Tolerances

While equations shape thinking, workshops and labs shape hands. Mechanical engineer training thrives where metal chips, polymer filaments, and test rigs tell the truth that models cannot fully capture. In a well-run lab sequence, students start with basic measurement and safety, then progress to machining, welding fundamentals, additive manufacturing, and assembly practices. They learn not only “how” to make a part, but “why” certain processes yield better surface finish, tighter tolerances, or higher fatigue life. A simple bracket assignment becomes a masterclass in manufacturability: the same geometry machined on a mill, printed via fused filament, or cast in a simple mold will have different tolerances, anisotropy, and post-processing requirements. Seeing these differences in hand builds intuition no textbook can replicate.

Quality and metrology are central to this phase. Vernier scales and gauge blocks teach the limits of measurement; dial indicators reveal runout; surface plates expose warp that eyes miss. Students practice geometric dimensioning and tolerancing on real parts, discovering how a single datum misinterpretation can scuttle an assembly. Lab notebooks—kept with time-stamped entries, sketches, and hypotheses—train disciplined thinking. In strength-of-materials labs, tensile tests produce stress-strain curves that reveal elastic modulus, yield strength, and ductility; in fatigue tests, S-N curves bring life prediction into focus. Even failures are rich teachers: a brittle fracture line under a microscope speaks volumes about microstructure and processing history.

The workshop also teaches safety culture and process flow. Good programs emphasize:

– Machine safety: guards, lockout/tagout procedures, and pre-use inspection habits.

– Material handling: heat-resistant gloves, proper storage, and labeling of stock and scrap.

– Clean work: tool organization, chip cleanup, and coolant management to prevent contamination.

– First-article inspection: measure, correct, then run the batch.

– Root-cause analysis: five-whys and fishbone diagrams to solve recurring quality issues.

Compared with purely theoretical training, this environment inculcates respect for variation, a realistic sense of time and cost, and the creative humility to redesign when a process says “no.” In the end, tolerances stop being numbers on a drawing and become a shared contract between design and production.

Digital Competence: CAD, Simulation, and Data Literacy

Modern mechanical engineering is inseparable from digital tools. Parametric CAD turns sketches into living models that update intelligently when dimensions change. Finite element analysis helps estimate stresses, deflections, and modes before metal is cut. Computational fluid dynamics gives early insight into pressure drops and thermal mixing. Multibody dynamics predicts motion and loads in mechanisms. Yet the goal is not button mastery; it is model credibility. A credible model is built from appropriate assumptions, conservative boundary conditions, mesh independence checks, and correlations to experiments when possible. In training, students should learn to ask: What is the driving physics? What simplifications retain the essence without masking risk?

Practical digital fluency means treating models as part of an engineering data system. That includes file hygiene (clear naming, version control, and change notes), attribute-rich part libraries, and traceable inputs. It also means modeling cost and schedule alongside stress or temperature. When a design change saves material but adds assembly time, the “right answer” lives in a multi-objective space. Coursework that integrates simple cost models, energy use estimates, and maintenance impacts makes students ready for cross-functional decisions. Data literacy rounds out the toolkit: cleaning test data, fitting curves responsibly, and reporting uncertainty with clarity. A well-made plot—axes labeled, units clear, confidence intervals shown—speaks the quiet language of credibility.

Digital deliverables worth practicing during training include:

– A revision-controlled CAD assembly with exploded views and bill of materials.

– An analysis report that documents assumptions, boundary conditions, and validation steps.

– A design history file linking decisions to requirements, test results, and risk assessments.

– Parametric studies showing sensitivities to key dimensions or material properties.

– Lightweight simulation models for rapid concept screening before detailed analysis.

Compared with ad hoc modeling, this disciplined approach reduces rework, eases manufacturing handoff, and supports audits. When graduates can both critique a mesh and defend a tolerance stack-up with data, they bridge the once-wide gap between the screen and the shop floor.

Industry Experience: Internships, Co-ops, and Capstone Integration

Industry exposure converts classroom knowledge into momentum. Internships and co-ops place trainees inside real schedules, budgets, and regulations, revealing constraints that rarely fit into problem sets. Typical placements run for a summer or a full semester; extended co-ops may cover six months or more, deepening responsibilities from test execution to fixture design or process improvement. Capstone projects, often sourced from external partners, add a simulation of the product life cycle: requirements capture, proposal, design freeze, prototype, test, and iteration. The combination builds confidence and a portfolio that shows not just what you know, but what you shipped.

An effective search for industry experience is strategic. Students who treat the process like an engineering project see better outcomes:

– Define target sectors early: energy, manufacturing, mobility, medical devices, robotics, or HVAC.

– Map required skills to each role and upskill intentionally before interviews.

– Prepare concise, visual portfolios: three projects, each with problem, constraints, decisions, and results.

– Network through faculty, professional societies, and local meetups to reach hiring managers.

– Set weekly goals during the placement: deliverables planned Monday, outcomes reviewed Friday.

Performance in the role matters as much as getting the role: communicate progress proactively, document decisions, and ask for feedback that can be translated into portfolio evidence. A one-page post-mortem after each project—what worked, what failed, what you would change—compounds learning.

Capstone integration amplifies this growth. Teams that run gated reviews, maintain a risk register, and pilot test early tend to finish with working hardware rather than late-stage surprises. Simple metrics help: track requirements coverage, test pass rates, and design changes per week. In many regions, publicly available labor data indicate that early practical experience correlates with faster entry into full-time roles and stronger starting compensation. The reason is straightforward: employers can see your decision quality under real constraints. When training includes this bridge to industry, graduates step into their first roles not as passengers but as contributors.

Your Roadmap and Conclusion: Skills, Ethics, and Lifelong Momentum

A mechanical engineer’s education does not end with a degree; it evolves with technology and responsibility. Early-career engineers benefit from structured onboarding: learning company standards, quality systems, and safety protocols. Many regions offer licensure pathways that include supervised experience and examinations; pursuing credentials signals accountability and opens doors to roles that require signing authority. Short courses, micro-credentials, and standards training keep skills fresh, from advanced manufacturing methods to reliability engineering and lifecycle assessment. Reading habits matter too: standards updates, technical journals, and failure analyses sharpen judgment more reliably than chasing every new buzzword.

Ethics is not an abstract add-on; it is embedded in daily choices. Selecting a factor of safety, reporting a test that contradicts prior results, or escalating a potential hazard are ethical acts. Training should include case studies where the technically correct path conflicts with short-term convenience, and where the public interest guides the decision. Sustainability is increasingly integral: material selection, energy efficiency, and design for disassembly are no longer optional considerations. Systems thinking helps navigate trade-offs—lightweighting that reduces operating energy might increase manufacturing complexity, and the right answer depends on use phase dominance and recyclability.

To turn intention into action, build a simple cadence:

– Quarterly: choose one deep skill to sharpen and one adjacent skill to sample.

– Monthly: dissect a published failure analysis and present lessons to peers.

– Weekly: practice clear communication—one executive summary and one annotated figure.

– Daily: track decisions in a design log with assumptions and open risks.

– Annually: reflect on portfolio breadth, ethics moments faced, and impact delivered.

This cadence, paired with mentorship and community, sustains growth. If you are an aspiring or early-career mechanical engineer, your roadmap is clear: ground yourself in fundamentals, make and test real parts, model with discipline, seek industry contexts where decisions carry consequences, and hold your work to ethical and societal standards. Do this consistently, and you will build not just employability, but the kind of engineering judgment that earns trust and shapes resilient, useful products.